About

Slavery Images: A Visual Record of the African Slave Trade and Slave Life in the Early African Diaspora

This educational resource is a two-part website created for teachers, researchers, students and the general public. It exists to assist anyone interested in visualizing the experiences of Africans and their descendants who were enslaved and transported to slave societies around the world.

This website is a digital archive for hundreds of historical images, paintings, lithographs, and photographs illustrating enslaved Africans and their descendants before c. 1900.

This visual record has been decades in the making, and it continues to grow. To advance common aims, Slavery Images has partnered and aligned with the mission of UNESCO's Slave Route Project: Resistance, Liberty, Heritage.

The Handler-Tuite Image Database

In the 1980s, Jerome S. Handler, a professor of Anthropology and pioneer in the digital humanities, began amassing photo slides of historical images depicting enslaved Africans and their descendants. By the late 1990s, Handler organized their digitization, generated metadata and put them online with the help of Michael Tuite, a former director of the University of Virginia's Multimedia Resource Center - now known as the Digital Media Lab and/or Institute for Advanced Technology in the Humanities. For more than a decade, Slavery Images resided on servers at the Virginia Humanities (formerly Virginia Foundation for the Humanities); and the website operated in partnership with the University of Virginia Library. In 2018, following Handler's retirement, the website migrated to the University of Colorado Boulder's Office of Research Computing and Center for Research Data and Digital Scholarship. For more information, please read the Project History and/or connect with our Contributors and Partners.

The Hander-Tuite collection was first selected from a wide range of sources which illustrate the forced migration of millions of enslaved people who were forced to travel great distances, oftentimes across the Sahara Desert, Mediterranean Sea, and the Indian and Atlantic Oceans. Slavery Images makes every effort to ensure bibliographic accuracy and the correct identification of both primary and secondary sources from which the images have been obtained, as well as correct identification of the area, country, or region to which the image refers. The dates we assign to each image may refer to the date an image was published, or at other times to when an author visited an area; in other cases, we could only assign a general time period. Despite efforts at bibliographical and chronological accuracy, errors remain, and we welcome any comments, suggestions, or corrections. It is necessary to emphasize that little effort is made to interpret the images and establish the historical authenticity or accuracy of what they display. To accomplish this task would constitute a major and different research effort. Individual users of this collection must decide such issues for themselves.

The Making of Slavery Images

Jerome S. Handler

April 14, 2017 (revised December 3, 2018)

In a sense, the website began at Southern Illinois University, Carbondale (SIU-C) in the late 1980s. At the time, I was a Professor of Anthropology at SIU-C, and had introduced an undergraduate Anthropology course, which was to focus on the everyday life of enslaved Africans and their descendants in the Americas. At the time (as it remains today), this was not a conventional course topic in Anthropology. The course was first taught in the fall of 1988 and was given once, perhaps twice, afterwards. I attempted to illustrate every lecture with images, particularly those depicting the everyday life of the enslaved, a goal that was only partially achieved. Utilizing a variety of well known published secondary sources, images were selected and the help of SIU’s Learning Resources Services (located in Morris Library) was enlisted to produce slides of these images. I was naïve in approaching visual images of slavery in published works and to the sources from which they were derived. I had no other intention than to give the students some visual perspective on the topics discussed in class; no thought was given to the historical accuracy of the images or the sources from which they were drawn. The upshot of this is that about 100 to 150 slides were acquired; these formed the core of the website to be developed in later years. I retired from SIU in the fall of 1995 and moved to Charlottesville, Virginia to take up a fellowship at the Virginia Foundation for the Humanities (VFH), today Virginia Humanities.

After several months at the VFH (Sept.-Dec. 1995), I returned to Southern Illinois and then came back to the VFH in Sept. 1996, this time staying eight months--until May 1997. During my first stint at the VFH, I had an idea for an NEH summer institute on the slave trade, particularly the middle passage, and during my second stay I approached Joseph Miller (a prominent historian of Africa, then on the faculty of the University of Virginia) and asked him to collaborate. Miller agreed and suggested a somewhat different, albeit related, focus for the Institute. We applied for a grant to do an NEH Summer Institute for College Teachers. With their support, the Institute took place for four weeks during the summer of 1998 at the VFH and co-directed by the two of us. During the Institute, “ROOTS: the African Background of American Culture Through the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade,” I gave a slide-illustrated lecture, using some of the slides that had been collected earlier at SIU-C; this lecture focused on the lives of individual enslaved persons for whom I had images and biographical information from primary or secondary sources.

Someone, I no longer remember who (though it was probably Miller or a student in ROOTS), suggested that the whole slide collection should be scanned/digitized. At the time, I did not fully understand what this meant, but I was directed to Michael Tuite, director of what was then called the Multimedia Resource Center and later, when it joined UVA’s library, the Digital Media Center (Tuite, with a PhD in Earth Sciences, left the Digital Media Lab in late 2006 and as of this writing is on the staff of the Jet Propulsion Lab, California Institute of Technology). (The Digital Media Lab was shut down in 2015 during a reorganization of the library.) Tuite scanned/digitized the slides and suggested creating a database and then a website to bring the images to the attention of a wider audience. Thus, the website or idea of the website was born. This was around late 1998 or early 1999, and in September 2000 the website was launched with about 150-200 images arranged in 10 categories.

Initially, neither Tuite nor myself had a clear idea of what we wanted to achieve, but the site continued to grow. By Nov. 2001, it contained close to 300 images; by spring 2002, 500 images. By August 2006, the site had grown to 1,200 images, by November 2010, 1,275, and in March or April 2011, it reached about 1,280 images, arranged into 18 topical categories, the number it has today. It should be stressed that the categories are not mutually exclusive, and many images could fit into several categories. Although the metadata are regularly revised and edited (up-dates are clearly indicated on the front page of the site as well on individual images), no additions to the database are planned. The database initially used was Filemaker but a few years after the site’s launch, MySQL was substituted.

In January 2007, the site took on its present domain name www.slaveryimages.org. It has a wide and geographically diverse audience, both in North America and abroad. The largest block of visitors are in the United States, but others range as widely as from Western Europe, including the United Kingdom, to Russia, South Africa, and Australia. Users include college/university teachers giving PowerPoint lectures in their classes, teachers in secondary schools, scholars publishing books or articles or giving lectures/talks at conferences, book publishers seeking images for their publications, museums wanting images for exhibitions, TV channels producing documentaries on subjects related to slavery, and lay persons interested in slavery or the history of their families.

The website is frequently visited. For example, over the six -year period, 2006-2011, when we began acquiring statistics, the site averaged about 12,500 unique visitors per month, never going under 12,000. During the 12-month period of 2016, the site attracted over 100,000 visitors, averaging about 8,380 a month; over 80 percent of these were “new visitors.”

From the very beginning of the site there was a clear division of labor between Tuite and myself. He was entirely responsible for the technical aspects of the website: he designed it, built it, maintained it, uploaded images, converted jpg’s into tiff’s, did trouble shooting, etc. From a technical viewpoint, the site is his.

On the other hand, I was responsible for the “scholarly” portion of the website. I located the images through research in scores of libraries and archival repositories (a significant percentage of the images were acquired at the University of Virginia Library [its own holdings or through interlibrary loan], The John Carter Brown Library, the Library Company of Philadelphia, and the Library of Congress). I selected the images to be placed on the site; obtained permission, when necessary, for their use; arranged for their scanning or photographing at the repository; wrote the textual material (metadata) accompanying each image; and developed the topical categories in which the images were organized (see section “Explore the Collection”). I continue to update the metadata when new information comes to light, when viewers offer suggestions or spot errors, or when scholarly publications appear that are relevant to a particular image.

The site was never intended to be exhaustive regarding African life in the Americas, but rather selective in the images chosen. And users have continually been encouraged to write if they could correct or amplify any of the metadata.

Of fundamental importance throughout the development of the website was the inclusion of accurate bibliographic information. This was essential. And this accuracy was mandatory so that scholars or others could trace individual images and judge their value for their own purposes. Every effort was made to identify original sources of images published in secondary works or shown on commercial or other websites. It was discovered early in the research that commercial photo sites can frequently be unreliable when citing, even if they bother to do so, sources used in their slavery images; and authors/publishers who use these images compound the errors when they uncritically depend on such sources (for example, J. S. Handler and A. Steiner, “Identifying pictorial images of Atlantic slavery: Three case studies.” Slavery & Abolition 27 [2006]: 49-69).

In the early phases of the site’s development, several criteria guided the choice of images. The fact that I am a cultural anthropologist very much informed these criteria. The criteria were subjective and often arbitrary, and shifted over time. However, certain criteria were constant.

- The site should give a Diasporic perspective on the lives of enslaved Africans and their descendants in the New World; i.e., it should show the diversity and range of enslaved populations and avoid overloading on, for example, the U.S. antebellum South (the conception of slavery held by most North Americans).

- The site would be selective in the images that are displayed and not include every image located of enslaved Africans or even of pre-colonial continental Africans. Selectivity was subjective and often arbitrary, especially in the early phases of site development.

- Ideal images were those based on eyewitness drawings, even if embellished by engravers/publishers before publication, emphasizing cultural features, social life and material culture. Such images were especially desirable if they were accompanied by a textual description, e.g., a visitor to Brazil who describes as well as illustrates the scene he witnessed in a slave market. This emphasis also applied to images of Africa, to give some idea of the societies from which enslaved Africans originated.

- Images that were patently racist and grossly portray Africans or their descendants in racist stereotypes were not considered for the site.

- Images should achieve a topical balance as much as possible, that is, not to overload the site with images of people working in sugar or cotton, among the most common images available. Social topics, e.g., funerals/burials, religious rituals, family life were the most difficult to acquire; images showing economic activities and such aspects of the slave society as physical punishments, escapes/fugitives, and revolts were easier to obtain. In all cases, efforts, not always realizable, were made to achieve some geographical and temporal balance.

Over time, other considerations were applied:

- With a few exceptions, images that are political satires, cartoons, etc. were ignored. Legions of these were produced during the emancipation/abolition controversies in, for example, Britain and the U.S.

- Images were often included which were evocative of a particular cultural practice or event, even though their authenticity was problematical, i.e., the image was not based on direct observation or was a fabrication loosely based on some historical event. A good example, often reproduced in historical works of the United States with the implication that the event was directly observed by the artist, is an image of the first landing of enslaved Africans at Jamestown, Virginia, an event that took place in 1619; the image itself, however, was created around 1900 by a well-known American illustrator.

- Sometimes images were included, particularly of early African cultures, which were fanciful depictions by European publishers to illustrate the perspectives of European travel accounts of Africa. As an interesting aside, early images of Africans by Europeans generally do not have the racist depictions, which were to emerge during the era of the Atlantic slave trade and particularly in the 19th century as Europeans colonized Africa.

- Increasingly, an effort has been made to put the image in context, using direct quotations from the sources or providing other contextual information. Revisions to the metadata often involve these considerations.

For many years, the website was on a server at the University of Virginia Library, but this server was increasingly aging and was phased out of commission. The site was then transferred in early 2016 to a server utilized by the Virginia Humanities.

* Many thanks to Professor Paul Lovejoy who encouraged me to write this account and offered his comments for improvement. Also to Will Rourk, Miya Hunter, and Professor Joseph Miller for their assistance in helping me with “memory issues.”

Jerome S. Handler Interview

Earlier Website Versions

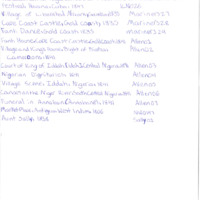

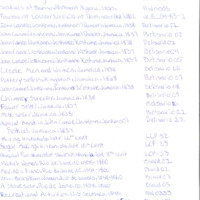

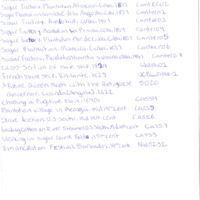

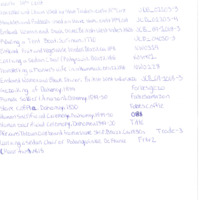

Jerome S. Handler's Research Notes

Acknowledgments of Website Migration 2

Henry B. Lovejoy and Kartikay Chadha

December 19 2023

We are delighted to announce the migration and recent launch of SlaveryImages.org. One of the pioneering projects in the field and created by Jerome Handler and Michael Tuite, the SlaveryImages digital archive offers open-source access to historical images, paintings, lithographs, and photographs illustrating enslaved Africans and their descendants before c. 1900.

As part of the UNESCO's Routes of Enslaved Peoples project, supported by University of Colorado Boulder, Virginia Humanities, University of Virginia, SSHRC, Mellon Foundation, and NEH, SlaveyImages is an educational resource for teachers, researchers, students, and the general public. The new website visually captures the experiences of Africans and their descendants who were enslaved and transported to slave societies around the world.

Since 2007 SlaveryImages has attracted over 1.5 million new users and averaged about 15,000 per month, while page views totaled above 12 million hits and has become a very important digital project across all humanities research. This relaunch is an upgrade brought to you by WWW, under the umbrella of RegeneratedIdenitites services for African Digital Humanities projects providing cutting-edge technological support for knowledge dissemination and digital sustainability.

Acknowledgments of Website Migration

Henry B. Lovejoy

December 15 2018

Taking over the direction of Slavery Images is an honor. This website has continuously been a resource I have relied upon to conduct research and teach the history of the African diaspora. I am thrilled that Jerome Handler has entrusted me with the further development of this website. To recognzie his contributions, I immediately renamed the database of historical images as the "Handler-Tuite Image Database" to honor their pioneering work in the digital humanities. Over the past few months, I have been thrilled to collaborate, discuss and strategize future directions of the website with Handler. The passing down of legacy websites from distinguised scholars to younger generations. The sustainability of digital projects is problematic because without support, funding and maintenance, websites can disappear and die. In taking over this project, I am grateful for Handler who has also transferred to me a network of people in Virginia (explained in more detail below) who continue to demonstrate their long-standing interest in preserving and improving Slavery Images for future generations. I am particularly thankful to Matthew Gibson, Will Rourk, Worthy Martin, Trey Mitchell, William Brandon, among others at the University of Virginia and Virginia Humanities for their help and advice with the transfer and ideas related to the future development of this website, especially in terms of introducing me to IIIF and CS3DP.

The University of Colorado Boulder (CU Boulder) has generously supported the re-development of this website. When I arrived to CU Boulder in 2016, my colleague and retired professor, Peter H. Wood, had already been working with a group of local K-12 teachers to develop a curriculum on the "History of Racism." To achieve this goal, Allyson McDuffie (Director of Education and Outreach at Trimble), Richard Hassler (GeoSpatial Market Manager at Trimble) and Fran Ryan (former CEO of Impact on Education) were working with a team of teachers and adminstrators from the Boulder Valley School District. During several meetings and consultations, I quickly realized that Trimble had been organizing the scanning of heritage sites related to the history of the slave trade, including: Natchez Historical Park (Mississippi), McLeod Plantation (Virginia), Annaberg Plantation (St. John, U.S. Virgin Islands) and a replica 18th-century ship used in Hollywood.

With the support of the History Department at CU Boulder, CU Boulder and Trimble Inc. hosted a meeting to discuss the ideas and difficulties of hosting, displaying and maintaining 3D data online. Presenters at this workshop included: Fran Ryan (Impact on Education), Bryn Fosburgh (Vice President of Trimble), Jane Landers (Vanderbilt University), Walter Hawthorne (Michigan State University), Henry Lovejoy (CU Boulder), Dean Rehberger (Michigan State University), Ethan Watrall (Michigan State University), Thea Lindquist (CU Boulder), Shelley Knuth (CU Boulder), Allyson McDuffie (Trimble), Richard Hassler (Trimble), Jobie Hill (Saving Slave Houses) and Peter Wood (CU Boulder). Other participants included: Myron Gutmann (CU Boulder), Debbie Hamrick (CU Boulder), Thomas Hauser (CU Boulder), Christopher Hespe (Aspen Creek Elementary School), Andrew Johnson (CU Boulder), Elizabeth Fenn (CU Boulder), Shawn Halifax (McCleod Plantation), Kristen Lewis (Boulder High School), Paul Lovejoy (York University), Bud Pope (CU Boulder), Leslie Reynolds (CU Boulder), Sherri Sheu (CU Boulder), and Debby Weiss (CU Boulder). This meeting resulted in excellent brainstorming on how to develop this website and maintain 3D data over the long term. The challenges seemed insurmountable and the project stalled throughout most of 2017.

Once Handler decided to step down as director of Slavery Images in early January of 2018, Google Analytics demonstrated how successful this website had become. Since 2007 (when the analytics code was first added to the site), Slavery Images had attracted over 1.5 million new users and averaged about 15,000 per month, while page views totaled above 12 million hits. These statistics do not take into account the period between 2000 and 2007. The majority of all users fell into the age demographic of primarily university and high school students.

Acknowledgments of Slavery Images

Jerome S. Handler

March 17, 2017.

Early funding for acquiring images came from the Department of Anthropology at Southern Illinois University (Carbondale). Funding for acquiring images in the middle and later stages of this project and for designing the website came from the Virginia Foundation for the Humanities (now called, Virginia Humanities) through support from the National Endowment for the Humanities. These funds were later supplemented by a research fellowship from the Virginia Foundation for the Humanities, a Cotsen fellowship awarded by the National Humanities Center, a fellowship from the Library Company of Philadelphia, and several fellowships from The John Carter Brown Library at Brown University.

We are indebted to many individuals for their help over the years. Many slides that were scanned at the Digital Media Lab of the University of Virginia Library were originally made by the Learning Resources Services at Morris Library, Southern Illinois University; others were later done by the University of Virginia's Alderman Library Copy Center. A considerable number of images were also scanned directly from published materials in the Digital Media Lab and by the Department of Special Collections, University of Virginia Library.

The professional and technical staff of the University of Virginia Library have been extraordinarily helpful and congenial. We are particularly grateful to Michael Plunkett (former Director, Department of Special Collections), E. J. Jordan, Regina Rush, Felicia Johnson, Margaret Downs Hrabe, Jeanne Pardee, and Bradley Dangle (at one time or another on the staff of Special Collections), Erika Day (formerly film librarian, Robertson Media Center), Rick Provine (former Director, Robertson Media Center), Scott Silet (formerly, Reference Department), Patrick Yott (former Director, Geospatial and Statistical Data Center), and Douglas Hurd and Lewis Purifoy (Interlibrary Loans). Thanks also for technical assistance to personnel who, at one time or another, have been associated with the Digital Media Lab: Jason Bennett, Jama Courtney, Lisa Gottschalk, Bruce Johnson, Kirk Moore, and Will Rourk. Over the years, Monnica Terwilliger and Rai Wilson, as Graduate Research Assistants, provided technical and research assistance, and Christopher Avery, Emilia Braun, Miya Hunter, Anna McCrerey, and Annis Steiner, at various times undergraduates at the University of Virginia, diligently assisted with the research in locating images and compiling background information, as did Francesca Brady, at the time an undergraduate at Brown University.

Juanita Anderson gave us the final title for the original website (since retitled in its present form). Stephanie Berard, Kandioura Drame, Robert Fatton, and Benjamin Guichard assisted with translations from the French; Susan Maycock, Luciana Wlassics, and Lauren Wencel provided translations from the Italian; Kelly Hayes and Carla Larangeira translated from the Portuguese; Carola Wessel from the German; Cornelia King and Zack Matus from the Latin; and Blanche Ebeling-Koning and Dennis Landis from the Dutch. Special thanks to Kent Mullikan (National Humanities Center) for his assistance with funding, and to Phil Lapsansky (Chief of Reference, Library Company of Philadelphia) for his prodigious efforts in identifying African American images which considerably aided our work; also, for his continuing willing support in dealing with a multitude of bibliographic and other research queries. We are also grateful to John Van Horne (Director), James Green, Cornelia King, and Charlene Peacock, who consistently provide a congenial environment in which to do research while Handler held a fellowship at the Library Company of Philadelphia. Equally congenial and helpful was the staff at the library of the Mariners Museum (Newport News, Va.), including Susan Berg (Director), Gregg Cina, Claudia Jew, and Cathy Williamson. Norman Fiering (former Director and Librarian, The John Carter Brown Library), was an early and strong supporter of this project, and we are particularly obliged to Susan Danforth, Susan Newbury, Dennis Landis, Richard Ring, Leslie Tobias Olsen, and Heather Jespersen, at various times on the staff of the John Carter Brown Library, for their consistent and often indispensable help in a variety of matters. The JCB's website, Archive of Early American Images, has been a major resource in our efforts to identify and describe many images placed on our website. We also thank Leslie Fields and Marilyn Palmeri of The Morgan Library & Museum for their willing cooperation and assistance with our project.

Kenneth Bilby, Christoper DeCorse, Mark Hauser, Barry Higman, Neil Norman, Merrick Posnansky and David Moore lent or gave us copies of their personal slides which we scanned, and Cristian de la Carrera gave some crucial assistance in scanning images. Carroll Johnson (Library of Congress) and Hugh Alexander (The National Archives/Public Record Office, London) graciously helped in obtaining a number of images, Elizabeth James (National Art Library, Victoria and Albert Museum) and Allison Callender (Barbados Museum), helped with a variety of research issues.

Kenneth Bilby, Douglas Chambers, David Eltis, David Geggus, Erik Gobel, Wim Klooster, Jane Landers, Robin Law, Paul Lovejoy, Pat Manning, Charles Medina, Neil Norman, Ugo Nwokeji, Robert Paquette, Katherine Prior, Mariza de Carvalho Soares, James Sweet, John Thornton, and particularly Joseph Miller, gave counsel and advice on substantive and interpretive issues. Others who have helped in various ways are acknowledged on various entries. Finally, we are especially grateful to Judith Thomas, former Director of the Robertson Media Center at the University of Virginia Library, and Robert Vaughan, former President of the Virginia Foundation for the Humanities, for their continued unfailing practical and moral support.

Contributors

Project Director

Henry Lovejoy, Director of Digital Slavery Research Lab, Associate Professor of History, University of Colorado Boulder

Website Development Team

Walk With Web / Regenerated Identities

Kartikay Chadha, CEO

Maria Yala, Senior Web Developer

Dvir Raphael Malka, Junior Web Developer (2023-2024)

Aadil Baig, Junior Web Developer (2023-2024)

Leighanna Estrella, Web Designer (2023)

Graduate Research Assistants

Vachan Aswathanarayana, Graduate Research Assistant of Computer Science, University of Colorado Boulder (2018-2020)

Tiffany Beebe, Graduate Research Assistant of History, University of Colorado Boulder (2018-2019)

Travis May, Graduate Research Assistant of History, University of Colorado Boulder (2018-2019)

Creator

Jerome S. Handler, Senior Scholar, Virginia Humanities; Michael Tuite

Partners and Affiliates

Copyright of Historical Images

These images were obtained from primary sources made before 1924 and they are in the public domaine and free to use, republish and modify. If you believe Slavery Images violates copyright in anyway, please contact us directly so that we may arrive at a solution and/or remove the appropriate images as required.

Additional Copyright Information

Slavery Images cannot grant or deny permission to publish or otherwise redistribute any materials. Most of the historical images displayed on this website were created before 1923, meaning they are considered to be in the public domain under the "Fair Use" clause in U.S. Copyright Law. Slavery Images also recommends taking into careful consideration the Library of Congress’s guidelines related to Copyright and Other Restrictions That Apply to Publication/Distribution of Images: Assessing the Risk of Using a P&P Image, as well as the library's Legal Disclaimer.

In most cases, the sources we have used to digitize images are available in several, if not most, major research libraries, particularly those with large collections of materials related to the history of the African diaspora. Users interested in obtaining higher resolution images from original sources are advised to locate sources themselves through conventional searches of online catalogs of major university or public research libraries, as well as WorldCat/OCLC. We intentionally provide no additional information on the location of sources within the metadata because multiple copies likely exist. In some cases, however, certain images have restricted distribution rights, especially materials derived from rare books and special collections. Whenever applicable, Slavery Images usually acknowledges these specific restrictions within the metadata of a specific image. In such cases, the acknowledgement of a particular library in our metadata does not mean this library is the only place the image is located. For more information about where specific images displayed on this website originated, we have included for your reference a copy of Jerome Handler's Research Notes. His notes, which include printouts of Handler's library searches, were digitized "as is" from two boxes organized alphabetically according to the author of a resource within which an image, or multiple images, were displayed or published.

Contribute to Slavery Images

If you have images you would like to donate and license to Slavery Images, please contact Henry Lovejoy who will provide you with a link to a crowd-sourcing form for you to fill out and submit the highest resolution copy of the image in your possession. Please ensure you look at samples of some of the images because Slavery Images wants accompanying metadata for our audience who can learn about the image. We would expect a small paragraph, as well as a license to republish the image for open-source educational purposes.

We do not provide a public link to our crowd-sourcing form to guarantee that there is a level of expertise surrounding the submission and creation of metadata. All submissions will undergo revision from members of our advisory board and directors.

For related news, events, and updates please follow us @walkwithweb.